/ Rémie Vanderhaegen / remie.vdh@gmail.com / +32495660697 / Rémie Vanderhaegen / remie.vdh@gmail.com / +32495660697 / Rémie Vanderhaegen / remie.vdh@gmail.com / +32495660697 / Rémie Vanderhaegen / remie.vdh@gmail.com / +32495660697 / Rémie Vanderhaegen / remie.vdh@gmail.com / +32495660697 / Rémie Vanderhaegen / remie.vdh@gmail.com / +32495660697 / Rémie Vanderhaegen / remie.vdh@gmail.com / +32495660697 / Rémie Vanderhaegen / remie.vdh@gmail.com / +32495660697 / Rémie Vanderhaegen / remie.vdh@gmail.com / +32495660697 / Rémie Vanderhaegen / remie.vdh@gmail.com / +32495660697 / Rémie Vanderhaegen / remie.vdh@gmail.com / +32495660697 / Rémie Vanderhaegen / remie.vdh@gmail.com / +32495660697 / Rémie Vanderhaegen / remie.vdh@gmail.com / +32495660697 / Rémie Vanderhaegen / remie.vdh@gmail.com / +32495660697 / Rémie Vanderhaegen / remie.vdh@gmail.com / +32495660697/ Rémie Vanderhaegen / remie.vdh@gmail.com / +32495660697/ Rémie Vanderhaegen / remie.vdh@gmail.com / +32495660697

September 2023, Brussels

Dear Rémie,

The words of our conversation have sunk to the bottom of this Indian summer, where they slowly died off to then sprout into other, new words — the words you are reading here and now. Suddenly, I am that dentist from your drawings. I am the one who puts words in your oeuvre’s mouth during my writing operation. I cross the threshold; I move beyond the breaking point.

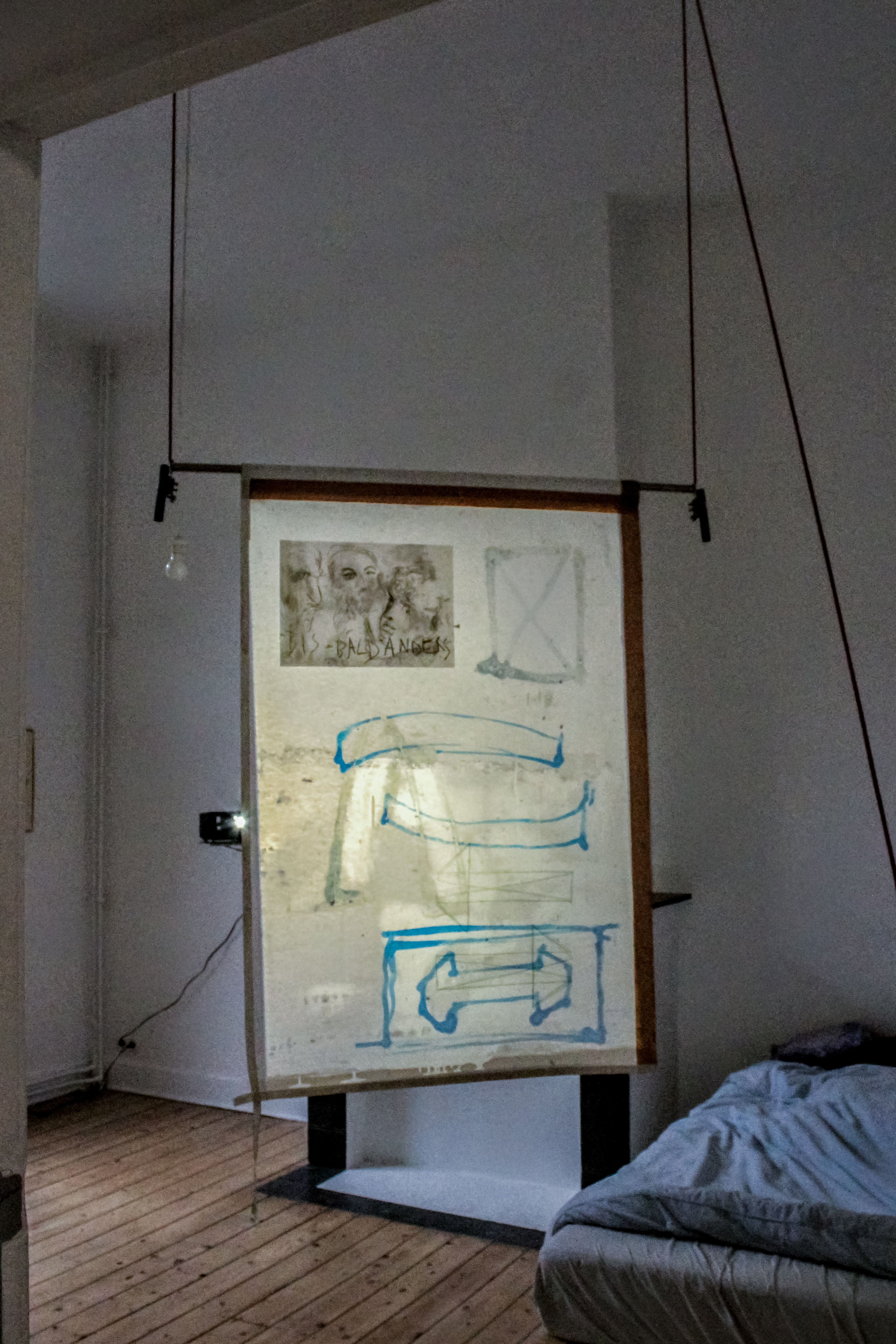

Herms and Terms revolves around terminology, language and interpretation. Your works — in themselves a translation of your drawing practice into installation art — allude to the “unstable nature of reality, its elusiveness and ambiguity,” as you write.

The image of a will-o’-the-wisp shining a blue-white light above a swamp to lead travelers off the right path looms in my mind. Lights of the Devil, they are also called. Irrlichter, dwaallicht, hinkypunk, Feu follet, Feugo fatuo. As I approach, I get misled, and the will-o’-the-wisp appears elsewhere.

I sometimes appreciate being misled, and take pleasure in pursuing what is elusive. After our conversation, I leafed through the facsimile of art historian Aby Warburg’s Bilderatlas Mnemosyne (1927-1929): a series of wooden panels on which he combined black-and-white photographic reproductions, photographs, advertisements, news reports, diagrams, sketches, postcards and other images into clusters. Within each cluster the images related to each other through associations, but there was no real common thread. Warburg continued searching feverishly for ways in which motifs emerge in human imagery and how they travel through times and places. His project was never completed, and Warburg died while chasing.

Will-o’-the-wisps are said to be wandering souls, stranded in the limbo between life and death. Stranded on the threshold of an unknown afterlife.

I briefly looked it up, but in Warburg’s Bilderatlas, Hermes is conspicuous in his absence. However, the motifs of “herma” or “herm” based on his effigy roamed equally between Greek Antiquity and Renaissance. The sculptures consisted of elongated, vertical pedestals culminating in heads (and sometimes a torso). Sculptors depicted male genitalia on the pedestal itself; the rest of the body remained abstract. Their function was apotropaic: like bouncers-avant-la-lettre, the Herma guarded entrances to streets, temples, tombstones or houses, keeping Evil outside for good.

The will-o’-the-wisp is lingering at the gates of limbo: according to legend, because a promise is not yet resolved, or a task not yet completed.

Just like the herma, many everyday structures around us function as thresholds: turnstiles, service counter windows, synthetic gloves in plastic boxes. (Exhibition texts sometimes too, I believe.) They all guard points of transition without us realizing, impose a direction for us to follow and dictate the rhythm of our existence. It is a matter of not taking their “silent dominance” (as you call it) for granted. In your sculptures – a contemporary version of the herma – you look for the breaking points. Fragility still lurks behind the clinical and flawless masks of the counters, the turnstiles and the gloves. You steady the pedestals dangerously, showing their fragile composure. Hammers that can break the windows are lying around. In case of emergency.

When emergency breaks law, can we take up the hammer? When do we dare to put our hands in the boxes with gloves?

If Herms and Terms were an ode to Warburg, one panel would collect images of dental practices. However, this is not about “the dentist”, but about the idea of the dentist as intruder: just as several images from the Middle Ages onward suggest that dentists rob their patients, the images from your research are about dislocating, disrupting and an uninvited entry. More importantly, they are about “putting words in one’s mouth”, getting someone to utter something without them having a say in it, and about language and power structures escaping our will.

The terms, I realize, are not so different from the “herms”. The power of words is fragile. It can fade if we misunderstand their fluid nature and if dialogue is no longer possible in the entrenched relationship between signifier and signified. Then, in the autumn of their existence, words die and lose any relevance.

I continue to wander, also in this text.

As a writer, I am supposed to be able to juggle with language and words. Unlike you, I do not have dysphasia, and so my relation to language is different, but my writing also arises from a struggle with words that simultaneously clarify and obscure, with words that keep slipping through our fingers. The question “What is hidden in images, in emotions and in the unspeakable between the lines?” is a rewarding driving force though. Something will always get away from us, and that is just as well.

All the best,

Dagmar

Text written by Dagmar Dirkx

with the support of the flemish goverment

![]()